Kondratieff Waves and Innovation

In 1925, Nikolai Kondratieff published Major Economic Cycles,

in which he presented statistical analyses of grain prices, wages, industrial

production, and trade indicators in leading industrialized nations. His

findings indicated that there existed a “long and regular wave” that could not

be fully explained by the conventional 4-to-10-year business cycles. This

phenomenon is known as the Kondratieff Cycle (or Kondratieff Wave).

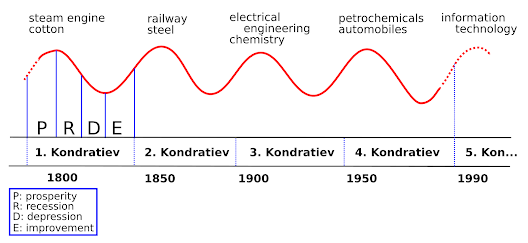

Kondratieff identified four key phases within each wave:

- Expansion: The economy enters a boom phase driven by innovative technologies or production methods.

- Prosperity: New industries grow rapidly, leading to surging demand for labor and investment.

- Recession: Markets become saturated and technology reaches its limits, causing growth momentum to wane.

- Depression: The overall economy falls into a slump, structural adjustments take place, and the seeds of the next innovation wave are sown.

|

| Source: Kondratiev Wave (Wikipedia) |

The Five Long Waves in History

- First Wave (ca. 1770–1830)

- Centered on the Industrial Revolution, sparked in Britain by the steam engine, spinning machines, and mechanization technologies.

- Expansion: Rapid growth in textiles and iron, with the development of transportation infrastructure (canals).

- Recession/Depression: Intensified competition, speculative bubbles, and external shocks such as the Napoleonic Wars led to a downturn.

- Second Wave (ca. 1830–1880)

- Characterized by explosive growth in railroads, steel, and coal.

- Expansion: European and American railroad network expansion, large-scale financial investments.

- Recession/Depression: The railroad bubble burst, the 1873 financial panic, and subsequent deflation caused by capital withdrawal.

- Third Wave (ca. 1880–1930)

- Driven by electricity, chemicals, internal combustion engines (automobiles and aviation), and the telephone.

- Expansion: Around 1900, the widespread use of electricity, telephones, light bulbs, and automobiles accelerated, with the United States establishing a system of mass production.

- Recession/Depression: The 1929 Great Depression, the collapse of the gold standard, and the rise of protectionism.

- Fourth Wave (ca. 1930–1970)

- Centered on Fordist mass production, petroleum, consumer electronics, and postwar reconstruction.

- Expansion: The United States dominated the global economy; automobiles and household appliances became mainstream; consumer society boomed.

- Recession/Depression: The oil shocks of the 1970s (1973, 1979) and stagflation.

- Fifth Wave (ca. 1970–2010)

- Led by information and communication technology (ICT), semiconductors, computers, and the internet.

- Expansion: Commercialization of the internet in the 1990s, the digital revolution, and globalization.

- Recession/Depression: The early 2000s IT bubble burst and the 2008 financial crisis.

During the expansion phase, new technologies drive

large-scale investment, productivity improvements, and overall economic growth,

leading to prosperity. However, in the recession and depression

phases, overinvestment, speculative bubbles, and market saturation often

trigger major structural adjustments and prolonged slumps. In essence, each

wave reflects how new innovations emerge, expand the market, and ultimately

face maturity and decline. Capitalism feeds on human ambition and technological

progress, but it can also fester. When the “boil” grows too large, it must be

lanced and disinfected with economic “antibiotics.” Although this is how

capitalism survives without collapsing, the burden of these painful

restructuring processes often falls on the general public, particularly

lower-income groups.

In this regard, Kondratieff Waves align with what Joseph Schumpeter

called “creative destruction.”

In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942), the Austrian economist Joseph A. Schumpeter defined creative destruction as ‘the process of breaking down and replacing existing structures in order to create something new.’ Schumpeter viewed capitalism as a dynamic system driven by the constant pursuit of innovation. In this system, innovation creates the ‘creative’ aspect, while destroying the status quo or established markets represents the ‘destruction’—ultimately opening up a new phase of growth.

Connecting Kondratieff Waves with Schumpeter’s concept of creative

destruction, we see that during the long upswing (prosperity),

innovation from the previous wave spreads throughout the economy, generating

broad markets and employment. However, as the cycle moves into a downswing

(depression), existing industries and technologies reach their limits, no

longer delivering high returns. This naturally leads to recession and

restructuring. In other words, businesses or technologies unable to maintain

competitiveness face obsolescence or liquidation.

Different Types of “Innovation” in Each Kondratieff Phase

- Upswing : Stable Destruction

- Incremental Innovation

- In the upswing, previously introduced technologies become mainstream and spread across industries and society. The “destruction” that occurs here is largely incremental, upgrading existing systems rather than replacing them outright. Because the infrastructure is well-established and organizational growth is rapid, there is a preference for incremental innovation that adapts to existing structures.

- Downswing : Radical Destruction

- Fundamental Restructuring and Radical Innovation

- During the downswing, there is usually a strong desire to maintain or optimize existing industries and technologies, even though profitability declines. As it becomes increasingly difficult to address new challenges with old methods, the necessity for finding fresh avenues for growth intensifies.

- Although it can be difficult to justify large-scale investment amid restructuring, a crisis often magnifies the need to change paradigms, spurring radical innovation.

Ultimately, Kondratieff Waves remind us to think in longer time

horizons, revealing that the demand for “change” often peaks during a downswing

rather than an upswing. In an age of scarcity rather than abundance, “change”

requires more imaginative thinking—this is precisely where Schumpeter’s

principle of “creative destruction” becomes even more relevant. When the

once-solid order of the previous generation starts to show cracks—when crisis

looms—innovation becomes not just an option but a lifeline.

0 댓글